Introducing The Blinn Report

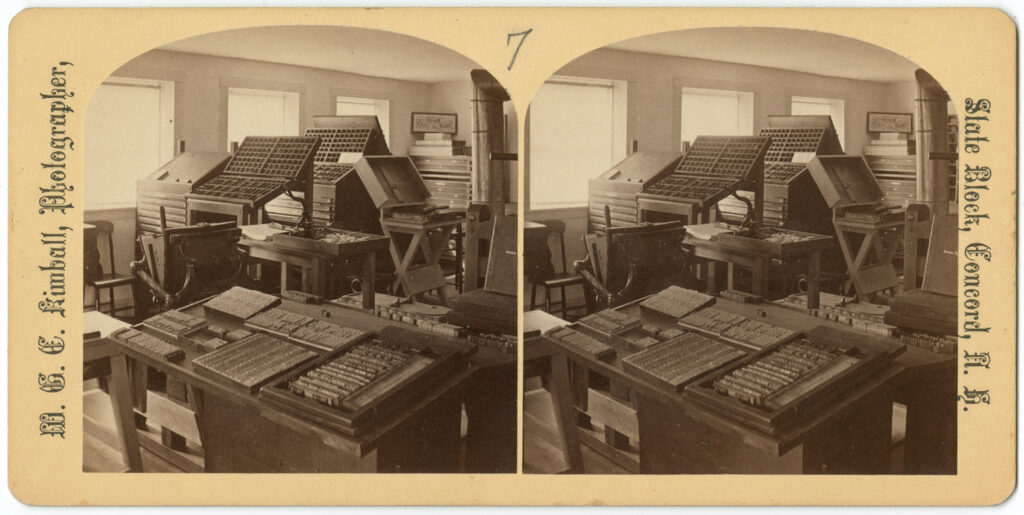

Shaker Elder Henry Clay Blinn (1824-1905) was neither a soldier nor a spy. Those are two roles the Shakers disavowed. But he was a tinker and a tailor. And a typesetter, printer, writer, editor, and publisher. He was a teacher and a beekeeper. His dexterous hands were, at one time or another, devoted to dentistry, cabinetmaking, and mapmaking. His mind’s work lives on in the works he wrote, including chronicles of life in Canterbury Shaker Village. Elder Henry even created a museum—what was then called a cabinet of curiosities. It included specimens of nature as well as manmade artifacts, telling the story of the Shakers and of the Shaker who collected its objects.

How fitting, then, to title our blog The Blinn Report. We hope we honor and exemplify Blinn’s curiosity as we highlight objects from Canterbury Shaker Village’s vast and varied collections—and the many, many stories these objects reveal about this long-lived utopian community. We hope, too, to elicit your curiosity about the Shakers.

It was curiosity—a “puzzle,” to use Blinn’s words—that led him to become a Believer. In late 1838, Blinn recalled, he “observed a man passing so quietly on the street and being dressed so differently from the other citizens that he attracted my attention, and at the same time awakened my mind an interest to know who he was and where he lived.” The man was dressed, “in part, like a Quaker, yet the people said he was a Shaker.” Seeking more information, fourteen-year-old Henry, with his mother, visited the stranger. What did Blinn learn?

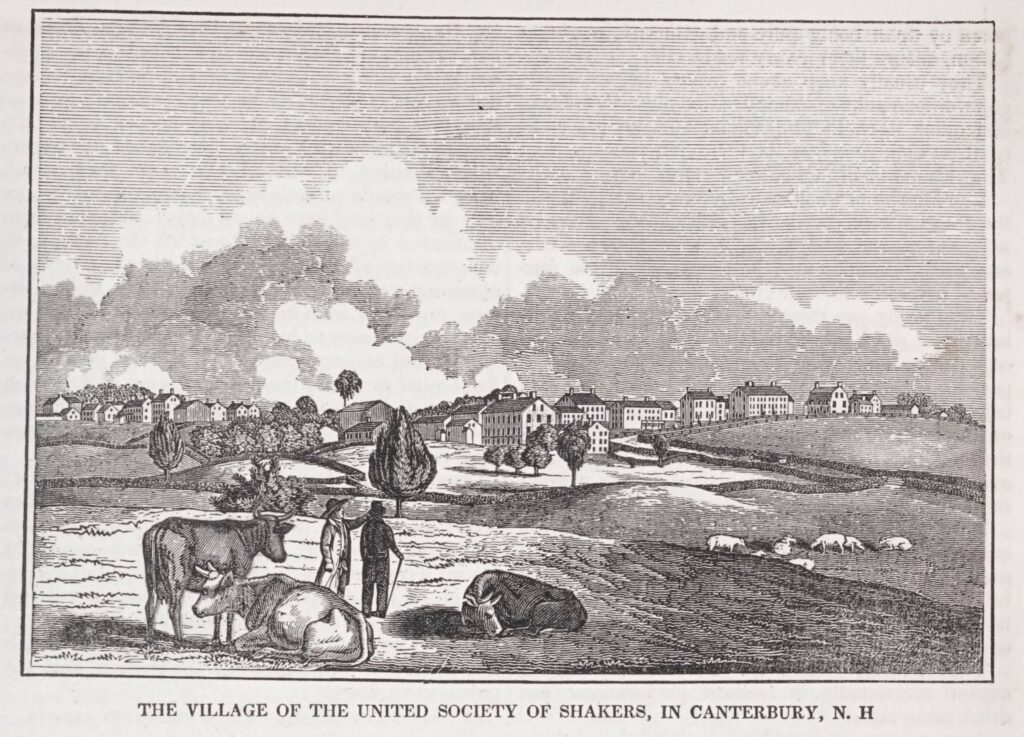

… I learned that the man was from Canterbury, in the State of New Hampshire, some 120 miles distant. He represented the Shakers as being a very kind and charitable people who were engaged in farming and manufacturing, also told us that they lived in large families, which sometimes numbered not less than eighty or one hundred persons.

His story was very interesting, as he told of the kindness of the people, of their religious services, of their schools, and of the fields, orchards and gardens; so that I became fully determined to accompany him to his home in New Hampshire.

And so, Henry did. For the rest of his life Blinn devoted himself to his faith and to his community. His “Autobiographical Notes” chronicles his life until 1893, but the Village’s archives and object collections help us to learn more about Elder Henry’s life and work. He will be appearing in this blog from time to time.

In the meantime, we offer this photograph of Elder Henry and his bees, among the budding trees of the plum orchard, the Hen House and Sheep Barn in the background. It is so fitting that this image was taken in the spring, a season traditionally associated with youth and innocent curiosity. Blinn’s white hair shows his age, but his sure stance and focused eye seemingly show him to be curious about something we cannot see. In the posts to follow, we hope to share with you the views and viewpoints, stuff and stories, of the Shakers and the community they created at Canterbury. Maybe—just maybe—we’ll find what Elder Henry was seeing.