With all that we know about the Shakers’ waking hours of work and worship, it’s time to ask how they slept. Did a day of physical labor and mental focus make for a restful night’s slumber? Did the more devout labor nightly about the state of their souls? What made for a comfortable bed, keeping in mind that comfort meant not only support but physical ease? What may we learn by exploring retiring rooms’ furnishings?

Big questions, to be sure. Let’s start with a remarkable and rare, green-painted wood bedstead in the Village’s collection.

Let’s also imagine how this bedstead would have appeared made up for rest. Cords were drawn tightly from side to side and from end to end of the bedstead,” Elder Nicholas A. Briggs recalled of the first bed in which he slept in Village in 1852. “Upon these cords reposed a mattress made of corn husks. In winter there were feather beds upon these husk beds. In summer the sheets were of cotton cloth; in winter they were of flannel.”

Sisters made the beds every day, but every Friday, according to Briggs, the beds remained “unmade all day with windows open for a thorough airing of room and bedding.”

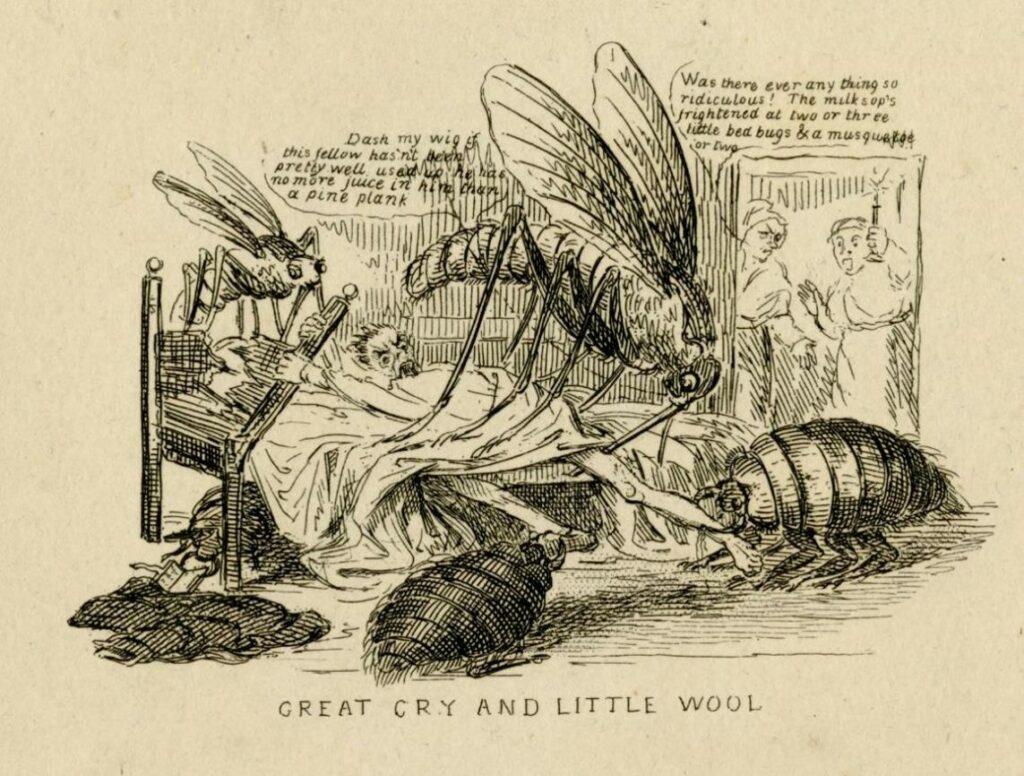

Airing bedding, especially when bedding was hung over the sills of open windows, revealed and killed vermin and bacteria. The organic materials of bedding made for attractive homes for all sorts of vermin, including bedbugs that also took up residence within the beds’ wood frames.

Could it be that the bedstead was painted green because it repelled bedbugs?

One of the nation’s earliest published household manuals, The American Frugal Housewife, first published in 1828, noted that “verdigris-green paint” was an effective bedbug deterrent. Its author, Lydia Maria Child, wrote:

Child added that “there are two kinds of green paint; one is of no use in destroying insects.” Only verdigris-green was useful. But really, it was likely the mercury (quicksilver) that did the trick—and it must have worked, for this advice appeared in many newspapers and household manuals for much of nineteenth century. The other green paint was known as chrome green, a synthetic paint gaining popularity in the 1840s. From Child’s advice, you would think that it is the chemicals of the colors that makes the difference and repels bedbugs.

During the Shaker “Era of Manifestations,” the main ministry at Mt. Lebanon, New York, issued a new set of Millennial Laws. These 1845 documents–each copied by hand for each Shaker community–covered religious belief and rituals, interaction with non-Shakers, and daily life.

One order was to paint bedsteads green.

Our green bedstead was made at Enfield Shaker Village. Enfield Shaker Museum curator Michael O’Connor pointed us to an 1844 article in The Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, in which a North Family sister there is credited with inventing the green paint bedbug remedy. This sister told the correspondent that “they have proved [the remedy] for the last fifteen or twenty years, and during that time not even one straggling ‘bed bug’ has been known to make his appearance.”

Michael O’Connor tells me he contacted historic paint conservator Susan Buck, and she told him that the chemicals in verdigris and chrome green paint would not kill or repel bedbugs. In 1994, Buck sampled and studied paint use in Canterbury Shaker Village. She found usages of verdigris-green and chrome green. She also found chrome yellow paint on retiring room floors. The Millennial Laws also included the order to paint the floors “in dwelling houses, if stained at all, … a reddish yellow,” so vermin control may also be a reason for that choice of color.

But what if it wasn’t chemicals but rather color that repelled these bloodsucking creatures of the night?

This is the finding of a 2016 study by entomologists who found that bedbugs are attracted to surfaces painted red and black but are repelled by yellow- and green-painted surfaces.

So, could it have been that the Shakers incorporated the common belief and practice of using green paint for bedsteads into the Millennial Laws of 1845? If we understand the Shakers’ emphasis on order and efficiency as a means to devote more time to worship God, green bedsteads represent a way in which bodily comfort, as well as the sisters’ time, was considered.

If anything, perhaps the Shakers rested more easily in the notion that they could keep vermin from invading their sleep.