Remember the weekend of the Great Freeze in early February? Any great change in temperature and humidity results in possible problems with a blocked drain and plumbing pipes—and for Canterbury Shaker Village’s unparalleled historic collections and structures. The Great Freeze required the Great Inspection of storage spaces, attics, basements, and cellars.

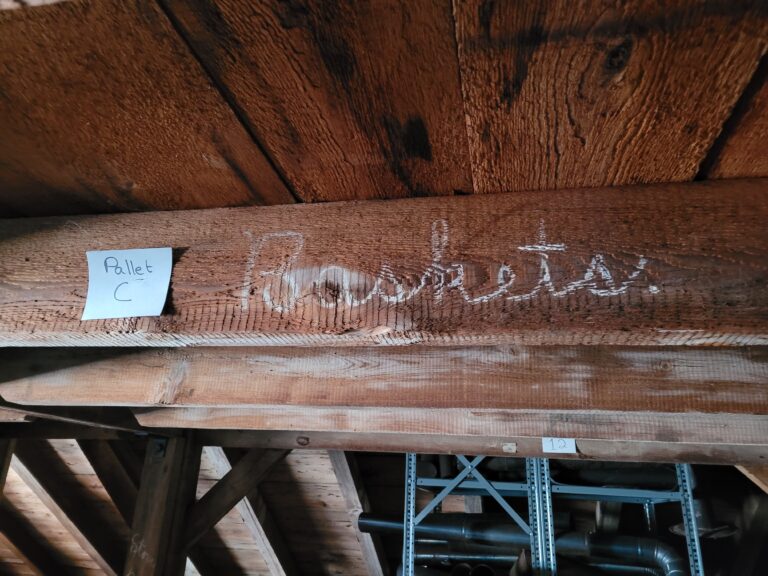

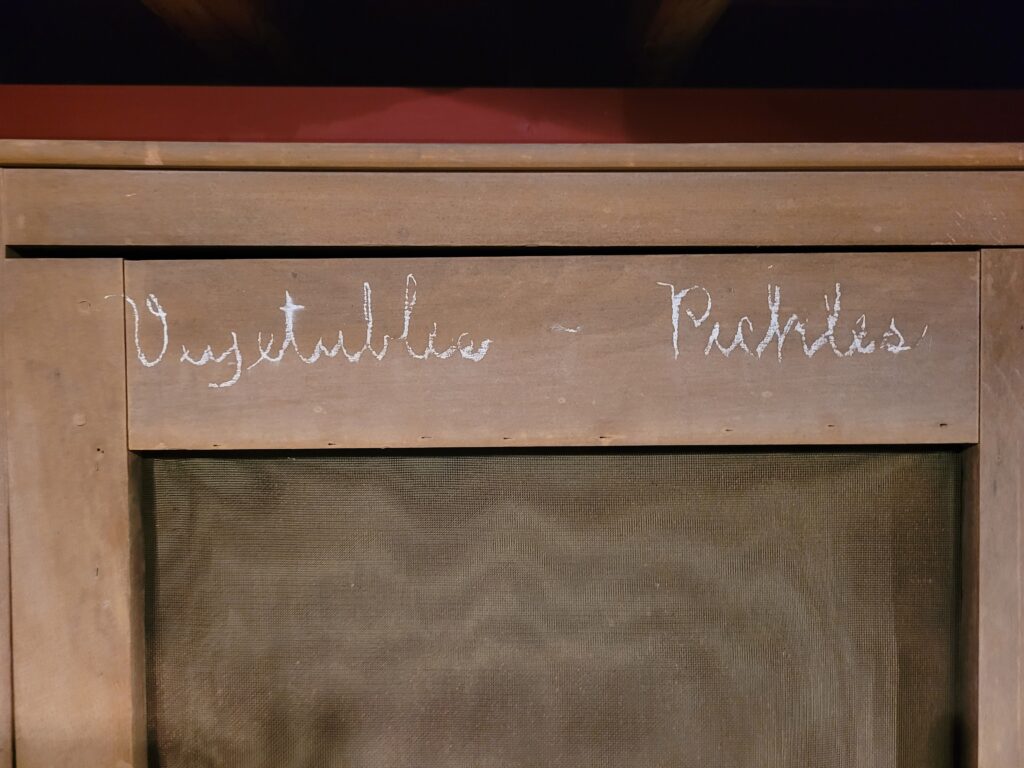

We aimed our flashlights at ceilings and roofs, door and window frames, and pipes. But in the Laundry our flashlights caught words written neatly by hand: Baskets, Corn Poppers, Handles for Mops, Chests, to list but a few. The order we find in the precision-built wood drawers and closets of the Sisters’ Attic in the Dwelling House finds it parallel in the finely written cursive script ordering the attic space of the North Shop.

Isn’t it always the case that when you see something new (to you) you see it everywhere? We made our way to the Carriage House, finding more specimens of handwriting penciled on a case piece used for paints storage and chalked on a food safe. Then there was the insistent—and larger—script on several doors. Someone in the past had consistently forgotten to shut the door!

Who wrote these words that ordered objects and people? Shakers? Their hired help? Later museum employees and/or volunteers? Why use handwritten signs when the Village had a Print Shop? And think about hand-made signs today: we invariably use printed letters. Most, but not all, of us learned to print before we learned to write.

An important clue to the dates of these inscriptions is the simple fact that they are written in “running hand” (linking a word’s letters together) and not printed.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries many people learned to write only a running hand. After the American Revolution, penmanship was a democratic practice, representing widespread literacy and participation in the body politic. Elder Henry Blinn recalled (in his Autobiographical Notes) that in 1843 “French’s system of penmanship” was taught at the Village’s school. This is likely James French’s A new system of practical penmanship, founded on scientific movements; and the art of pen making explained, for the use of teachers and learners, printed many times in Boston, Massachusetts, and Claremont and Lebanon, New Hampshire, after its initial appearance in 1839.

We have located copies of French’s manuals at the American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, MA) and are eager to undertake research there. In the meantime, we have matched handwriting on the walls and on furniture pieces to two different penmanship systems: Spencerian (taught 1850-1925) and Palmer (taught 1888-1950s). We are imposing order in our research, realizing that in the handwriting on the walls and furniture we have another form of valuable evidence of Shaker order and community life.