A visit to Canterbury Shaker Village’s collection storage means we are going to learn something new.

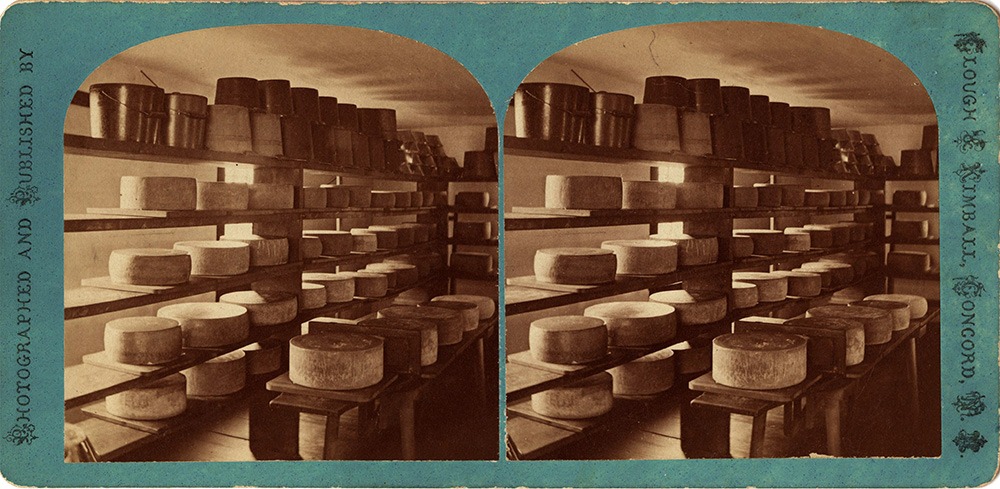

Such was the case (Case! Collections pun!) when we came across shelves of wooden containers. Different shapes, different sizes, different colors: it was a container beauty contest in which every single one, the product of the Shakers’ cooperage, was a winner. It reminds us of the topmost shelf of pails in the Village’s very clean cheese room, depicted in the 1880s in a stereograph.

Museums follow guidelines provided by object conservators and other professionals to ensure that these objects in storage remain whole and available for future generations. We throw around terms such as “off-gassing” and “inherent vice” to impress people, keep an eye on humidity and light levels, and are vigilant against vermin and dust.

We have gloves and we know when and how to use them.

It’s best to store objects made of like materials together, and that’s what we see in these wooden staved containers with metal bands. But arrayed in such a manner, we may also see how the objects resemble and relate to each other. Though alike in construction methods, these containers served different purposes. Firkins, narrower at the top than the bottom, were often waxed inside to store foods such as applesauce and butter. Maple sap buckets had metal hangers to attach them to trees. Lidded pails held food waste in the kitchen, and larger buckets and tubs held water for use in the kitchen and laundry. And we cannot forget the containers that strained: sieves used for sifting flour and washing fruits and vegetables.

The Canterbury Shakers built their first cooperage in 1795. By 1800, Elder Henry Blinn noted, the “first planing machine was made upright and used for planing staves and pail bottoms.” By 1814, the water-powered Turning Mill began to lathe-turn pails and tubs for the Shakers’ use and for sale. Numbers? Perhaps there’s a clue in one year’s maple sap production: In 1861, 700 buckets were used to gather 335 barrels’ worth of maple sap. But we also know that the Canterbury Shakers used buckets manufactured by the Shakers at Enfield.

How the Shakers determined how much a given type of container should carry is the question we are currently pondering. Related to market or government standards of weight? Based on what a human could carry? Or based on what the containers’ materials could bear in weight and use? How did they decide how many containers to make for a given use or task—or for sale? Likely all of these considerations mattered.

How the Shakers determined how much a given type of container should carry is the question we are currently pondering. Related to market or government standards of weight? Based on what a human could carry? Or based on what the containers’ materials could bear in weight and use? How did they decide how many containers to make for a given use or task—or for sale? Likely all of these considerations matter in our answers.

Containers such as barrels and firkins were necessary in transporting and storing goods and foods. But the simple recognition of storage tells us something else. Pails and buckets are efficient, in that they sport bail handles, so that one can be carried in each hand. Barrels roll, so that the heavy contents are more easily moved. When used for food storage, these containers aid frugality and security in their prevention of waste from spoilage.

In all, though, when we store anything, we are simultaneously assuming and assuring a future.

Museum collections are marvelous things. We ensure the future of historical knowledge and inquiry—and the ineluctable power of wonder—by preserving the objects of the past.

P.S.: For an explanation of Shaker cooperage that features both Enfield and Canterbury Shaker examples, please watch this video by Enfield Shaker Museum curator Michael O’Connor: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ghfGXJZ_mXI